He thrusts bright purses at me - ‘You buy!’ His body gives as I hug him gently - he is at first stiff, then he leans into me - I stand with him at my leg, my arm about his shoulders. ‘You buy.’ He smiles winningly.

What to do?

He has to learn to charm, to exploit tourists like me; I should just pay him and go, let him be pleased that his charm and skills have worked. But. But maybe it is MY ego, my wants that hold me back. I want him to know that I see HIM not the art, and that his targets are also human. I buy him mango juice but leave the purses.

you buy you buy -

in the street waif’s eyes

I see my son

There’s a bit missing were we visited an ancient nest of temples. Matthew will know where it was. He and Nad were keen to see it, but I found it oppressive. As if dark influences were sticking up from deep in the Earth. People paid them homage, but mechanically, with neither thought nor emotion, save their own selfish needs.

It was hot.

Matthew wanted to go in the main temple, but was denied. He stood on the steps wearing his white clothes, a red mark between his brows, and pleaded with the temple guardian. He got a leaf with soft pap on it, but no entry.

A dirty creek with a lake stood sullenly beside the numerous stone images and plinths. Nadashree and Krishnadas wandered, paying homage to them. People knelt on steps before a white-clad, bearded man. Children loitered near us, smiling shyly.

at the temple

children’s hands outstretched

for sweets

I was simply miserable.

The others sat beside me, trying to discover what was wrong. I gestured at the hills over to our right. There were houses there. That’s where I want to be, I said.

Matthew was quiet, thinking. He seemed to come to a decision. “Then we will go there, “ he said. “ We will go straight there, by taxi.”

We did. It was NAGARKOT.

Beside the Galaxy Guesthouse we met Dhurba. He worked there sometimes. We decided to stay further up the hill though, at The Hotel at the End of the Universe. Dhurba walked there with us, and later we sang and played in the courtyard.

…We sit around the table on a paved courtyard in Nagarkot playing African drums, a didgereedoo and guitars, singing bhajans. Here at The Hotel at the End of the Universe, we are two Nepalese, a Spaniard and two Australian Kiwis.

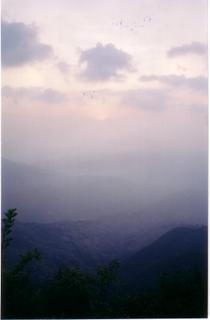

It is cooler here. The wind blows gently, mist obscures the Himalayas and settles into the valley. Conifers finger the air.

“Tomorrow if there is wind or rain we may see the mountains.”

5am. Dhurba wakes me, tapping quietly on my door. Neither Matt nor Nad are awake, though they were sure they would be, as arranged. Dhurba and I set off into the mist to his house in the valley. He has a school there and is keen to show me.

Dhurba on his way down to the valley.

Down and down we went into the valley, following water-eroded tracks cut deeply into the soil, scambling down rocks. At last we reached Dhurba’s place, nestled in fertile land surrounded by his garden and bounded by misty paddy-covered hills.

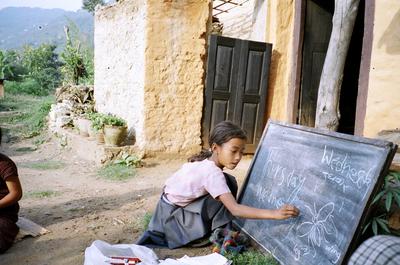

The children came. They knelt on the ground, in a row, in front of Dhurba‘s corrugated blackboard. They were ragged, dirty, and poorly dressed. All had bare feet.

****** Since my return to Australia I've been sending winter woolies for these children. He has eighteen altogether. If you'd like to help with clothes or if you could give any odd foriegn currency left over from travelling, leave me a message and I will send you Dhurba's address.

I should explain that education is not free in Nepal. These children come from poor families who can't afford the fees, so Dhurba teaches them as best he can but receives no payment for it.

The old woman and the chicken.

On our way back up the hills from Dhurba's house we stopped to catch our breath at a house with a dirt courtyard. I was reluctant to go in, but Dhurba and Matthew already had and were sitting in shade. An old woman who sat on the porch didn't seem to mind our intrusion, in fact she didn't look at us but continued to focus her attention on her hands. There she held a small chicken that had lost its eye. She gently smeared a green paste on the bleeding socket; the chicken's head was wet from her administrations and it cheeped quietly, but didn't seem to be in distress.

After some time she put the chick under an upturned raffia basket, with a hen. There was food there, and water; air circulated through the weave and it must have been cooler than it was outside in the hot sunlight; the chicken settled down quickly.

Nepalese courtyard

overturned baskets cheep

in the sun

Impromptu Music in the dust.

I forget how it started.

After we'd climbed out of Dhurba's valley, Matthew began to play his guitar at the top of the hill near the Galaxy. Before long a group had formed around my son, clapping and singing. Counter-rhythms and harmonies developed, we grew more animated. The group expanded; drums appeared, then a didgerdoo made of bamboo, and another guitar with its owner. We danced. Two women with headloads stopped a short distance away. They smiled at my Polynesian-influenced dances.

One by one Nepalese began to go solo. Tentatively at first, then with growing confidence, other voices joined in to give us folk-songs. We kept time, danced, smiled and felt the bonds between us grow as can only happen with shared music. We played on and on. Matthew squatted in the dust on the corner, Nadashri and I stood in front of him on the road and tiers of people crouched up the bank behind him or perched on rocks beside him. Someone brought me a wicker chair with stubby legs. The sun sank lower and lower.

In darkness we parted for food at last, agreeing to meet at a small shrine by the Galaxy Hotel to play music that night. But a wind came up, big time. We were all so tired that we stayed inside at The End of the Universe and crashed into bed. For the first time in over two years, I slept soundly.

0600 Thursday. Still in Nagarkot. But as I reach out with my awareness I know that we will leave today. I will shower and be ready when Krishnadas and Nadashree appear.

I was wrong. They slept til late and did not want to go. We talked about it though, and planned our next few days. We defined our objectives and our dreams as well. It was wonderful. ( I've erased most of it until I get it put into columns.)

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.

Nadashree:

*trekking in Nature.

*Good social culture.

Matthew:

*Kathy’s happiness. *Nadashree’s happiness * trekking

*Time with Nadashree, *To see big mountains hopefully

*To sing to Annapurna.

Kathy:

To find perspective:

*how to be happy * get wider view… go up mountains

* where I am going

Spend good time with Matt

* communicate well with Matt

Learn about relating; can I still do it?

See what my resources are.

To reconnect with life and find a new way of doing things.

* Dream/Vision: communicating with village people in a hut drinking warm drinks in a misty valley, with Yaks inside etc etc.

RESOLVED: To leave as early as possible for Mulkarkha. Try to do first stage - see how we go and re-assess.

(And so we did. )

Nadashree and I went walking to the village for a meal. Along the way we found people waiting for us and Krishnadas, to play and dance. “I like your beautiful dance, Mama.” They went to the liason point as arranged but of course we did not come last night.

Tonight though, there is a great playing beating piping singing at The End of the Universe.

It is windy again. The men sit out in the courtyard in the dark, drinking and making music.

Nadashree and I watch Johnnie Depp finding Neverland.

Dhurba gives us a card each, in farewell, but he is coming with us in the morning.

Friday. From NAGARKOT to KATHMANDU. (About 30 k.)

0540 Matt calls us to come and see - the sun rises gold behind a peak. We stand beside Kali’s temple above the hotel. Bells ring. In silence the mountain speaks.

We begin our walk. It will be more than 30k over two days. We walk, walk, walk. It is hard.

In the village Matt plays guitar. Children gather with wrapt expressions - he invites them, encourages, guides them to strum. We applaud. I give the cheerful shopkeeper a gift; some band-aides. She laughs, holds me enthusiastically in a prolonged embrace. As we leave she gives me a stick.

Deva Kumari

Deva Kumari

Again we climb.

Dhurba makes a mistake and leads us off course down and down into the valley. We see a poor house there. We pass Buffalo and goats as Dhurba speaks to a woman, to get directions. Children cluster under the open roof, their hair matted and salted with nits. There is a boy lying on the floor with a blanket over him, but I can see he is bare from the waist down. He has cerebral palsy, his legs hyper-extended and useless. He has never walked. That poor mother.

Up we go, and up. I nearly fall going around a big rock, my heavy backpack catching as I search for footing. I’m glad of Deva‘s stick. My breath comes hard, and for a while I am dizzy, my head aching.

At last we reach a mud-smoothed house at the top of our climb. We stay the night, grateful for food and rest, although the beds upstairs are nothing more than wooden benches covered with a thin mat, and the rooms smell of dirt and goats. Downstairs, the floors are pounded earth, there’s no electricity and no shower.

Matt again plays to the children here. Again the wrapt expressions, the shyness.

Nadashree and I draw on their hands with a biro. Birds, dogs, flowers, a deer for the girls. A moon and stars for a boy.

blue moon

inked on a child’s hand --

he holds it up

Dhurba cuts their nails when I give him my clippers.

The children are filthy. Their clothes are torn and stiff. I put cream on their faces, hands and feet. Their skin is wrinkled with accumulated dust. They are adorable.

We eat dhal bhat in the dark kitchen, by candlelight. We decide to go for the Jomsom trek, discussing it in private, then Matt asks Dhurba if he will come with us, as our guide. He is delighted, his face and body very expressive.

He and Raji sing and do hand-dances, ‘Risham piriri, risham piriri, oorayna jauki, dada ma bhanjyang, risham piriri.’ (Scarf in the wind. Blown away into a hill tree… scarf in the wind.)

I see a firefly! Like a spark flying! It attracts my attention; Raji catches it and shows me. Just an ordinary looking beetle when its light is out. Again, despite the early night and discomfort, I sleep until morning!

Sat. We awake in a Nepalese house. Dust.

The first thing I hear are chickens’ squeaking voices which I at first think is a mattress, as if I could forget the boards beneath me! Smallish chooks walk about with a purpose, orbited erratically by these excited chicks.

The sky begins to blush.

Matt runs up the beaten dirt path, “Come and look!” I grab the camera and follow….into forbidden land to the (army) lookout point. I take some photos though the viewfinder images are not brilliant. We will see.

bright

above the clouds --

mountains.

A plane flies overhead. I do a mime for the locals who have met here, waving my stick in an exaggerated manner. ‘Help! Help! Come and get me! Too much up! “ I lean on the stick, hobble like an old woman, lean forward on it, panting. This part at least is drawn from experience.

Walked a long hot day. Happily. Much laughter, especially from Nadashree, who is delightful. Much Spanish between she and Matt. Many stops, shade being of priority. Many drinks.

Matt lay down in shit,

Nad amused us by sticking a thorn to her nose, like a rhinoceros,

and Dhurba taught me the folk song, Resham piridi, complete with hand actions.

and Dhurba taught me the folk song, Resham piridi, complete with hand actions.

But Matt is disturbed by my brittleness. I wounded by his seeming judgement, cutting my feet away just as I begin to laugh. The rest of the journey heavy for me.

On and on, in hot sun. Matthew spotted a short cut, down into pine woods, the earth thick with accumulated needles. They three slept there, and so did I, briefly.

Then down and down for nearly an hour, to a waterfall. (The village only ten minutes away being a common fable.) Down and down for another hour. About 1000m in all. Through a checkpoint where we had to show our passports and pay a fee because we’d come through the National Park. Past the reserviour, under trees past strident insects, down beside the pipe, down towards Kathmandu. Down steps, passing between people squatting to prepare their evening meal, and the houses where they’d eat them.

Space, personal especially, seems to be perceived differently here to that in Western countries.

There is talk of ‘castes’ by Dhurba, who shows us a ‘lower caste’ man and a boy working a little metal forge by the path, but the other side of a fence. They squat in the dust, the boy with a bellows which seems to please the flame. Matthew and I chat to them. They look happy and strong. It must be hot work. We drip with sweat.

It stings my eyes.

Down down down forever down stone steps boulder steps concrete steps on down…. …to a squalid square bordered by shops beyond monsoon drains. There’s an unseemly scramble for buses. When we do get one, (packed in) it goes for some time through countryside picking up people without stopping entirely. Sacks are passed up. A young woman with a baby is jolted sideways, leaning against the steps; I rise in alarm to give her my seat but Dhurba has the aisle and he bids me to sit. Later he stands for a woman with children.

We stop at a Military road block. People stream off. A young man in Jungle greens enters the bus and scrutinizes us all. Our eyes meet briefly. He turns back down the steps, motions us on.

Beep beep blaring onward we go to stop again, abruptly. No petrol. The driver heads off with a yellow can.

Another bus arrives. We run, jolting along with backpacks dangling, me with my new stick. Tired legs. Light rain … paddy fields … Nadashree in, Dhurba in, me (bus moving) Matt behind; I lurch on wobbly legs, unbalanced, hurt my arm. These people do not care. Matt safely on board.

Hell. Strident discordant music. Heat dust noise swerving beeping filth. No headlights, no streetlights people everywhere -decay decay in sight and smell. Out into rain. Matthew and Dhurba find a taxi. “Metre on OK” he agrees.

Me a heap in the front, too tired to care, especially emotionally. Stunned and unfeeling. Cars flash headlights briefly at each other, beep! Dark figures in rain-slick streets -- everyone waits, swerves, steps back or away --street stalls clutter the road edges, shops yawn onto pathways and people people people moving sitting spitting speaking….

Matthew notices that the metre is not on as promised. He growls at the driver, who at once puts it on, but it already reads r60! Dhurba begins a loud and animated conversation with the driver, in Nepalese. He told us later that it went like this:

“ I am just ripping off these tourists; let me be!” “These are my friends of five years you do fair to them.” A traffic light! Aha! Another! Still no streetlights, and no more traffic lights. We stop. Dhurba’s angry tones, and Matt’s. R200 passed. The taxi gone.

We walk to our hotel. Himalaya Guesthouse. I climb the six stories to my room then down again to change money for Baba Dhurba. We are paying him in advance for two days as our guide, so he can go back to Nargakot tonight to get his things. We are to meet here tomorrow, at 3pm.

No linen on my bed. No pillow. No towel. And of course, no toilet paper. I shower, change, wash my clothes. Go downstairs for water to drink. Then I sleep on the bare mattress, an hour at a time.

SUNDAY I lie on my bed in dramatic inner dialogue. Perhaps I will go home. To Brisbane, anyway. If I annoy Matt it is the same situation as it was with my mother - better for Matt and all if I am gone.

At about 0930 Nadashree comes up. Cheerful, as ever Notices my lack of linen. I say it doesn’t matter. Later, Matthew comes up---again with the sheets-- and shortly a woman comes with linen. I help her make the bed. She protests.

11am-ish Matt, Nad and I take Nepali tea on the balcony by my room. We talk on my bed later, and I decide to stay. It seemed he was concerned that I was too ‘high’ and would soon crash. I told him that he precipitated the crash. If he says don’t be as I am it is confusing since what is, is. I am just this. He means no harm I know. I appreciate his concern, and he did not intend criticism, it seems.

We go for lunch. N goes back to leave a message for Dhurba to say where we are, but when I get back at around four pm there’s been no sight of him. I tell the hotel staff that I am upstairs in my room and to send my friend up to me when he comes.

7pm In fact, he has been three times, and was turned away each time! I see him by chance when I descend to enquire anew about him. He showers, we take tea, water, and watch TV. M and N do not come. At last, at 2030, we go to an Indian restaurant in an inexpensive part of town. Both the prices and the food are wonderful. By phone we learn that M&N are back, and we find them as we pass. Matt has bought a Gortex jacket, a flash walking stick, and Nad a drawing pad, for me. I’m touched.

We will go at 0600. For now, I sit beneath the fan, await their return. What to do? Where?

MONDAY. 0530. Up, showered. Light rain falls; it was intermittent during the night. Just as well I brought the linen woman’s washing in last night. Down to meet Dhurba and tell him the sad news re money. After yesterday’s shopping, we don’t have enough to pay for the bus. We visit Matt and Nat briefly. Matt is grumpy. We rush off to cancel our bus booking, “Half an hour away.”

Through filthy streets sloughed by rain we go, the streets already busy. Presently Dhurba exclaims in delight, recalling that his mother is here in Kathmandu and that he is free! We go to see her after the bus business is done. I have no money of course, just my book (The DaVinci Code) and jandles. He pays for my passage in a grimy little van/bus, then we walk beside a foul river. Children scavange there for string, and anything else that they can sell.

I see a mongoose! It runs across the path, then back. It is brown as dirt, rat-like but not a rat. Again we see it in a garden; it is weaselish. It looks at us, then it runs. So fast.

Dhurba only learned last night that his mother is here. It has been a year since last they met and she does not know that he is here in Kathmandu. He is very excited. We gain entrance to a coutyard via a barred gate and up the stairs he goes to cries of greeting. She is in a chair on the landing, a tiny woman clad in an orange sari. She is reserved, alert, beaming. He kneels, lifting her feet, which he kisses.

D has told the children I can draw. They bring exercise books and a pencil. I try. They are truly beautiful children. Faeryish. I am reasonably pleased with the results. D runs out to feed me small morsels of curry as I draw. Dhurba’s mother gives me a mango. I thank her holding the fruit as part of the blessing, namaste.

Back we walk through stench and litter, over the black river (clonk clonk clonk on sturdy boards) down streets puddled with fine black mud, where we are eyed, greeted, welcomed by locals. “You not tourist,” says Dhurba. Indeed. I am not.

We visit his brother’s wife. Again his mother’s feet are kissed. I sit outside the small sunken shop where I am sheltered from the rain that falls lightly, persistently. A chook limps through puddles, finding plenty of morsels. “It’s a good life for chickens here,” I say. “Not so good sometime,” says Dhurba; we nod and smile knowingly.

In a sentry-box a soldier sits atop the high brick wall opposite us. He has a rifle.

sentry with a gun --

morning glory falls

from metal spikes

I put my arm around Dhurba’s nephew. He leans lightly towards me. We touch heads, smiling.

‘Bok bok,’ I say to the chook. ‘Baaawk?’ It stops, eyes me. The boy chuckles.

Women pass in bright clothes, stepping over the mud. Their hair bounces in soft clouds, shining and clean. Some of them look at me in surprise, sitting with these Nepalese so casually. Everyone responds to ‘Namaste,’ especially when it is accompanied by the reverential gesture of praying hands and bowed head. ‘I salute the God within you.’ But it is a versatile greeting, too. As we leave, with bows and praying hands for all, I kiss his mother softly on her cheek.

Later back in the Guesthouse/hotel, Nadashree is pre-menstrual, restless and grumpy. Matt’s gut is a bit troublesome. He goes shopping. She does too, separately. I read on my bed.

Matthew comes back, lies on the floor, then the bed as we talk. I tell him I have realised that I jumped to conclusions re his concerns for me the other day. I apologise. He touched and grateful. We talk of language: simplification, melding, symbology and rhythm. I read from this diary, noting that I have simplified the language, as we do every day now. Then I notice that for the first time since we met at the airport, he is speaking in normal patterns again.

Nad comes back; she has brought a book for me -Paulo Caelho, The Alchemist.’ Also some muesli,(NOTE THIS MUESLI ) and milk. I have mango juice and chocolate that I got for children in the street, and of course, my mango gift. We order soup and toasted garlic bread, which is made downstairs and delivered to MattNad’s room. Matthew is still not well, but he takes two bowls. He’s sleepy. Nadashree is cute and giggly. She plays along with word games and fantasy so well. She is an actress by trade.

The guest-house owners’ daughter was married atop Everest last week, the first Nepalese woman to reach the summit. I look at dozens of photos while awaiting the soup. Her parents are so proud! She is on TV and in the papers and has gone to the US as a celebrity.

Our trek begins! We catch the bus early, and head for Pokhara, eight hours away. I make lists of images as we go, hoping for haiku.

monsoon -

soapy men beneath

the drain

himalayan rain -

the frail white net he flings

this fisherman

ancient silos -

wheat between the bricks

and in the fields

a fallen boulder

built into the wall -

surrender

yellow lanterns -

pumpkin blossoms

climb the wall

The bus climbs for hours, a concrete - coloured river churning to our right. The monsoon has begun; water cascades down the cliffs to our left and rushes away busily. Lovely vegetation grows everywhere; we are in jungle now, but fields of corn, bedraggled and sad-looking, appear more often as we gain altitude.

We stop at a road-side restaurant, and line up, several layers thick, waiting to served from a kind of Bain-Marie filled with asian food.

trees up the hill

from the river -

we queue for food.

It is still raining lightly so we sit beneath a raffia shelter to eat. Suddenly a girl pops up from the corn-field beside us. She looks me in the eye, making that dreadfully expressive gesture of carrying her empty hand to her mouth. Then she holds her cupped hands out, one on top of the other, to beg. I rise and take her omelete and noodles, then repeat that when she asks again.

begger in the corn -

openhanded blossoms

rich with sun

She holds her sopping dress out to show us she is wet. Dhurba buys her noodles as we run back to the bus.

At POKHARA I am disappointed because it is not what I expected. I had hoped that we would be beside our track, and that the mountains would be here to inspire us. Actually, I haven’t taken the time to know what or where Pokhara is, since Matthew’s had my Lonely Planet.

He and the others are excited though. The lake shimmers invitingly, but there are no mountains to be seen, and I think huh! not as nice as New Zealand.

I come upon a snake-charmer with his traditional cobra rearing from a basket as he plays an Indian flute. There’s a lovely python in another basket, and I pick it up, draping it around my neck as I caress its smooth skin. Nadashree takes pictures. The Charmer puts the cobra -basket over my head, inviting another photo, just as I spy Matthew and Dhurba’s faces. They are not happy, their expressions disapproving as they talk together. The Snake-charmer says, as he passes to remove the python, “ Five hundred rupees, Mam.”

“ Hah! Not bloody likely!” I say. “Look, I expect this is your livelihood, so I will give you something, but not that much!’ I peel out R30 for him.

Honestly! One can’t even admire a snake without incurring expenses!

But my little heart is wounded by Matthew’s disapproval. Down I go again.

So, when he and Nad fail to inform Dhurba and I that they intend to eat out on the lake, and we have trouble getting food, I go all sad. Dhurba conspires with me; they take no notice of him and he feels as left out as I do.

Matthew drops me in it, metaphorically speaking, telling some street hawkers that I will come and see their wares. “They are Tibetans, Mum, and one of them has cracks and stains on her hands from stringing beads.” They pressure me, and I buy some sandlewood beads, paying far to much.

We hire a boat as dusk falls, and row out near the middle. But the moon has come up, and it is full. It is 16 months tonight since Peter died. I am silent, enfolded in this moon.

Nadashree says that it is the Solstice and she wants to do a ceremony. She lights candles and invites us to write down things we want to release. The other three do that, reading them out then burning them, the ashes drifting out into the dark water.

We eat out there and paddle about quietly for an hour or two.

Dhurba sleeps on a mat outside, on the concrete. Matthew-Krisnadas and Virginia-Nadashree sleep on another even higher little roof above him, for a while, so they can see the stars. Then they come back to their room next door to mine.

In the morning Krishnadas rouses us with shouts of “Mountain alert! Mountain alert! “ We run out and watch as the Annapurnas flirt with us, revealing bits of themselves as they drop their veils of cloud. It is sunny, and my washing is dry. We have breakfast on the wee balcony outside our doors,

and, freshly showered, Nadashree examines Krishnadas’ hair for nits. She’s also had them for a day or so at least; we bought lice-shampoo in Kathmandu and I go through her long tresses now and again with the nit-comb I brought her. Some neat gift, eh? But rare, and welcome.

We shop and send emails, happily. Buffalo wander, trailing their warm smell. Soldiers and policemen with rifles patrol the streets, looking for Maoists. Barbed wire loops along roadsides and atop high walls. Children run up, handing us notes that say how poor they are and that we must give them money. We buy them biscuits and fruit juice instead. Then they want their photos taken. We do.

At Nadashree’s suggestion we hire bicycles and go a-riding. The seats are exceedingly hard, but to my surprise, I remember how to ride, and scarcely even wobble. Locals stare as I pass though; a 60year-old Western woman on a bike is not often seen, obviously. Shopkeepers wave and cheer as I go by.

We go up a hill around the lake to the north of the town. Wind of our passage cools us. We call to each other and ring our bells often as people wander in front of us. We are a team.

At the top of the hill, a crowd waits for a wedding party. The water is clear blue, the sun is hot. Nadashree wants to swim but my son tells her sternly it is not appropriate. Nepalis will be offended; we must respect them. Nad is not happy. I would also like to swim, but instead as we ride back, I look for some secluded place where we can fling ourselves unobserved. Nup. None.

I go to visit Baba-Dhurba’s friends, and we go back there for dinner. They are very welcoming, very warm. D translates for us. I am forced by politeness to drink a tumbler of home-made millet whiskey. Um…

Back at the hotel, we talk late, excited to be heading off for our trek proper in the morning! It is after 220am before I turn my light out. Dhurba takes his mat out to the roof.

At first light I go out to see the mountains, almost tripping over Dhurba who has moved into my room, his feet sticking out by the door. It has begun to rain, lightly sprinkling Amma satchels out on the roof. I guess M and N have been there already, and later, when rain comes harder, I retrieve them.

We order breakfast and eat it on the verandah, with Nepalese tea, before scuffying to pack in time to catch the bus.

“Marm, where are my boots?’ says D. They are gone. So are the sneakers I gave him, and all the boots as well, except Nadashree's.

Matt had sprayed them all with water-repellant last night, unbeknownst to me, and left them outside because they stank. Thieves have come this way, and we can not go today.

We notify the owner, and find a plank leaning against the wall to the roof.

Elizabeth had organised insurance for me; we examine the documents and see that it does not cover the theft of items left ‘in a public place.’ Never-the-less we decide to put in a police report, so Matthew tries to concoct a story whereby the boots were all inside. He is wearing his tee-shirt that says ‘Honesty.’ I tell him to look down.

We buy new boots. Nad and I set off on bikes to get ponchos, and I spill myself onto the road as a kerb kicks me. Tomorrow, then.